Mên An Tol: "unity and connection is what it's all about"

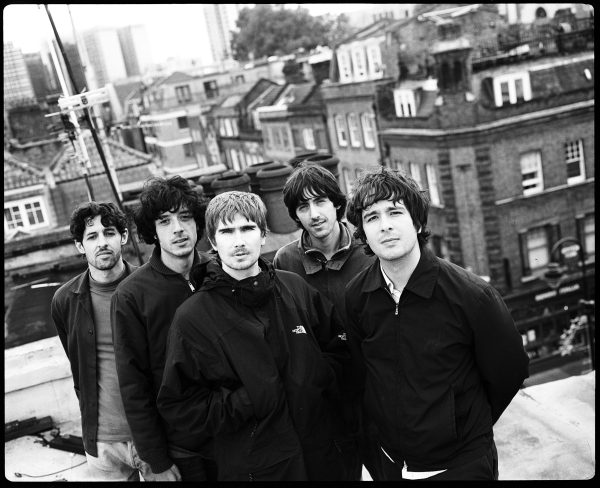

Five lads meet working in a South London pub and are united by their shared love of niche music. It might sound like the premise of an avant-garde Channel 4 comedy, but it’s actually the origin story of folk-rock five-piece Mên-an-Tol (frontman Bill Jefferson, mandolinist Felix Knox, bassist Max Silvey, drummer Tom Stevens and guitarist Robert Wiseman). Their second EP, This Land, was released on 26 September, just six months after their debut, The Country, in March; in the time in between, they’ve performed at Glastonbury, supported Miles Kane and The Libertines, collaborated with Carlos O’Connell of Fontaines D.C., and played their first gigs in mainland Europe. Not a bad year for a band that only played its first shows two years ago. We sat down with frontman Bill about everything from working with Carlos O’Connell to themes of togetherness and optimism in their music.

Your second EP ‘This Land’ has been out for a month now – how are you finding the reaction so far?

Really good actually. It’s nice to have all the songs out together so people can finally listen to it as a whole body of work. It also meant that we could get a vinyl press of the two EPs together. It’s like a full stop after the first recording sessions, so it’s onto a new thing now.

Is that your first time having music out physically?

Yeah, it is. It’s nice to have something physically to hold – I mean, I haven’t got a record player so I’ve still never actually listened to it on vinyl, but as I know it’s just a bit of a dream to have an actual physical vinyl. Makes a nice present as well with Christmas coming up.

Both EPs touch on themes like togetherness and optimism – ideas you’ve said are important to hold on to. Why do you think those values matter so much, and is it ever difficult to stay optimistic these days?

I think it’s natural for everyone to crave that feeling of togetherness, but over time we’ve kind of drifted away from it. There’s so much going on with technology and everything else that it feels like we’ve lost some of that connection – though I don’t think it’s ever really disappeared. Especially now, things are just so wild, you read the headlines and can’t believe half of it. But I never wanted it to be political – if anything, it’s the opposite. It’s not about politics, it’s about people. Togetherness, inclusiveness with all kinds of people. Especially now, when there are some really messed-up ideas going around in this country.

Mên an Tol played Left of the Dial a few days ago – how was that? Did the energy of the European crowd feel much different from the UK one?

It was amazing. We did three gigs in two days, and each one was really different. One was in a church, we had this huge church organ behind us and the pulpit right next to the drums. Then we did a gig on a boat, and there was a weather warning, so the river was really choppy – everything was swaying while we played. But there was a free bar, so you can imagine how that went. The last show was in a club that had been closed for nearly ten years, so people were just excited to be back there. It was a proper venue, something they’d missed for a while. The crowd wasn’t too different though. A bit taller, I suppose.

You’ve got a big headline coming up at the Lexington – how are you feeling about that? Does it feel like a bit of a milestone for the band?

Yeah, definitely. We’re feeling good about it, I’ve seen lots of bands there and, like you say, it does feel like a sort of definitely like a rung in the ladder. We do that gig and then hopefully do more with that bigger and better and stuff like that.

You grew up playing in traditional folk sessions in Cornish pubs. How do you think that background shaped the way you write and perform now?

I think that’s probably where a lot of the unity theme comes from, because so many of those pub songs have that thread of togetherness running through them. In terms of songwriting, it taught me not to overcomplicate things – it can just be verse, chorus, verse, chorus. A lot of folk songs are like that. Trim the fat, have something to say, and create a vibe. That’s really the focus of what we do.

Do you think modern alternative music has lost that people-first ethic?

Yeah, I think so. There’s a lot of bands that are, without naming anyone, very, like, intellectual. And whether it’s conscious or not, I think you do lose a level of connection with people listening to your music, because not everyone’s read whatever book or knows the artist you’re referencing. I think there’s a danger of it all being a bit tongue-in-cheek and intellectual, which we’re trying to not be – we’re trying to be honest and not anything too hard to grasp.

The name Mên an Tol comes from the standing stones in Cornwall, the EPs are called The Country and This Land, and the vinyl compilation is titled Regional Music. Is that intentional?

It started off as not being conscious. I was writing these songs and each one was called, like you say, The Country, This Land and stuff like that. And then I was showing it to other people in the band and they were like, what’s this all about – working titles or something? Once it’s pointed out, you sort of step back and realise that it obviously is a subconscious thing. I think it just comes naturally because I’ve lived in three different places, and it’s that unity thing where I don’t want to write a London-centric album, even though we all live here.

Having grown up in Cornwall, do you ever struggle with the pace or scale of London? Did it take some time to adapt?

Not really – as soon as you get to a certain age, you don’t want to be in a sort of sleepy town. Although I’m saying that, I’ve had some of the best nights out being in Cornwall. Some of the pubs down there, especially in Launceston where I grew up, are way more rowdy than London pubs. London felt kind of soft compared to a lot of places, actually.

Do you have to put much effort in to make sure you keep some of that Cornish roots in your music and approach since you’ve moved to London? Because obviously it’s two quite different things. How do you balance those?

I think, if anything, it magnifies it, because if you go away from somewhere, you romanticise and obsess about that place more. So that’s probably part of the reason why I’m writing the songs I’m writing – going back and referencing Cornwall because it’s held as an idealistic thing in my head now. I don’t write songs about Cornwall when I’m living in Cornwall as easily, I think it’s yearning to go back there that makes me write about it.

Your single Not Ideal was produced by Carlos O’Connell. How did that come about and what was he like to work with?

He came down to a gig during our residency at the Dublin Castle in Camden. I think someone must have sent him one of our tracks, probably NW1 because that was all we had out at the time. And then we got chatting after and realised we had a lot in common.

I didn’t really know that he did much production stuff, to be honest, but we just got chatting, sending each other tracks that we were into and stuff. And it became apparent that he’d be up for working on that track with us, so we went to the studio.

He’s obviously super busy, and had like two or three days here and there out of a schedule, so we did a couple of days in the studio and then he was away for like three months on tour, so it was quite spread out but the days that we did have were very intense. He was very generous with the little time he does have, and yeah, it was great – he magnified and pulled out the emotion that was there and kind of made it a bit more epic and potent.

Is there a lesson or a piece of advice or approach that he had that you think you’ll stick with for future recordings?

He has a real kind of laser focus on things, nothing’s like ‘that will do’ or ‘that’s just the drum part’ – he’ll ask why that’s the drum part and if that’s the best drum part. So I guess just questioning things a bit more and experiMênting.

You live with guitarist Robert from the band. Do you think that closeness of living together maybe makes you tighter on stage or helps the music at all?

Yeah, I do think so. He’s in the room next door and playing this violin he’s got, it’s quite annoying actually. Tom, the drummer, has lived in that room there before, and Felix, who plays the mandolin, has lived in it too. So we’ve all kind of lived together here in this flat above the pub, and it makes touring and being in a band a lot easier because there’s nothing we don’t know about each other.

You’ve recently come off tour with Cardinals and I read that you were thinking about taking some time to focus back on writing. What does that space look like now?

I’m writing every day and the rest of the guys are coming up with bits as well – it’s nice we can get into a studio and not necessarily rehearse for a gig, but just write together. That’s what we’re focusing on now – I just want to keep writing and get loads of songs. And then we can chat with some people and see what we want to do, because I don’t know if an album is a good idea or maybe another single while we keep writing the rest of the songs. But yeah, we’ve got a few new ones knocking about.

It’s two years this week since you first released NW1 – how has the band developed since then?

We’ve definitely got tighter playing together, and improved a lot in terms of equipMênt and sound. Because we’re not using the typical setup – things like mandolin and acoustic guitar in a heavier band – it took a while to really figure that out. But we’ve honed what we play and how we play it, and we’re better at writing together now too. Whenever we get in a room, we can come up with good ideas pretty quickly, and everyone’s a lot more open musically.

Where do you see Mên an Tol two years from now? What would you like to have achieved, and what does success look like to you?

Just to keep playing bigger and bigger gigs to more and more people. I like the idea of us being able to play these songs in a little pub somewhere people enjoy it and also can play on a huge stage and people enjoy it. I’d like to just keep scaling it up live-wise, because connection with people, for me anyway, is the sign of any success – that’s what it’s all about.

Words: Donovan Livesey Photo: Cuan Roche